13 Leopold Crescent: Lost Gateway to History

Seven degrees of separation between the original house at 13 Leopold Crescent and Queen Elizabeth II? A frivolous claim, perhaps—clues may be found in the following history—but the facts about 13 Leopold are more interesting anyway.

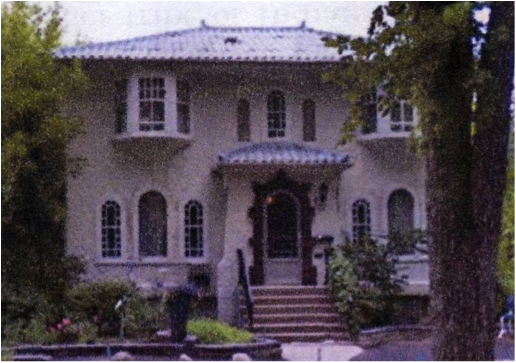

Exterior of 13 Leopold Crescent

But first the reasons behind the discovery of these facts. In early 2015, the City of Regina’s Planning Department received a demolition request from the new owners of 13 Leopold Crescent. This permission was required because the house was included in the City’s Heritage Holding By-Law List, and the associated bylaw states that owners of such a property cannot demolish it without allowing 60 days for the City to examine the merits of the request before granting or denying permission.

Because the City had insufficient information on which to base its decision, it contacted Heritage Regina (HR), a move that sparked an intense period of structural and historical investigations. The former led to suggestions of demolition alternatives, and the latter to a glimpse of Regina’s local history, which included the influences of nuclear fear and, in contrast to this dark spirit, architectural styles of the day.

HR’s ad hoc research committee began by looking at the ownership history of 13 Leopold Crescent, and discovered only three families within its 69-year history: vice-president of Waterman-Waterbury Manufacturing Company, Franklin E. Watchler and his wife, Agnes, 1945-1949; retired farmers Forrest Arthur and Nina Hendrickson, 1950-1976; and masseuse Donald Bennett and his wife, Beverley, a home decorator who latterly lived alone in the house until her death in 2014.

The architectural style and details of a building are another important aspect of any heritage assessment. Few Regina homes are of a pure style, but 13 Leopold Crescent takes the go-to descriptor “eclectic” to new heights, so conservation architect Bernard Flaman, author of Architecture of Saskatchewan: A Visual Journey, was asked for his opinion.

“The overall form of the house is traditional, and the white stucco, which could be related to modernism and also Spanish revival architecture, and faux-tile roof are vaguely Spanish,” Flaman wrote. “The glass block and curved element in the front relate strongly to streamlined architecture, while the corner windows on the second level are pure modernism, one of the most surprising elements of the house.”

Several early Regina homes exhibit elements found in the eclectic style comprising 13 Leopold’s unique facade: the 1930s aerodynamic concept of motion and speed as displayed by the Streamlined Moderne style; and the cubic composition, flat roof and corner windows of the Modernist style to follow.

The video below, provided by Capturing Reality Services, provides a 3D representation of the home before it was demolished.

Below is an excellent video on the Streamline Moderne style.

3116 Rae Street (1947)

2620 Regina Avenue (1942) was an early Modernist residence.

3076 Cameron Street (1946) retains its Streamlined Moderne curved glass wall.

3139 Cameron Street (1949) – Alterations detract from the original Modernist and Streamlined elements.

3116 Rae Street (1946) – Note curved corner and shed roof, with cornered windows.

3025 Garnet Street (1948) – A simple take on the cubic, flat-roofed Modernist style.

A heritage assessment of any building must include examination of the construction materials as well, and 13 Leopold was also interesting in this respect. In Regina, the presence of glass block, first used internationally in the 1930s and now in vogue again, usually marks a house as a 1940s build in Regina, and is relatively uncommon. Thirteen Leopold’s faux-tile, sheet-metal roof was another construction material not commonly found in Regina.

Few examples of the faux-tile, sheet metal roof covering 13 Leopold were found.

77 Leopold Crescent (1929)

77 Leopold Crescent (2015) – today, its metal roof replaced.

152 Connaught Crescent (1929)

2728 McCallum Crescent (1927)

Of great interest in a heritage assessment is the builder or architect of the structure in question. And this is where the previous work of one of the researchers was invaluable. Ross Herrington, who died suddenly in October, 2015, had already researched the Waterman-Waterbury Manufacturing Company, its vice-president Watchler and its unregistered architect Milton Campbell. Despite Herrington`s exhaustive lists, however, the connection between the W-W architect Campbell and the Watchler home could not be verified so the researchers could only suggest that Campbell was most likely the architect.

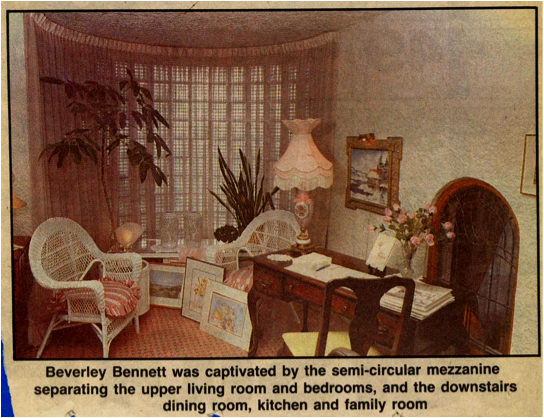

Because the interior details of a house may be of greater value than the exterior details, they must be assessed as well. While a personal inspection of 13 Leopold Crescent’s interior was not possible at the time, photographs of it were featured in a 1988 Leader Post article about the home and its owners, the Bennetts. They revealed an interior with art-plastered walls, Spanish Revival arched alcoves and doorways, and gumwood door and window frames, the latter uncommon in Regina.

The 1988 article also quoted Beverley Bennett’s assertion that the half-basement contained a “bomb shelter,” a rarity indeed. The son-in-law of the second owner of 13 Leopold Crescent scoffed at the idea, but a later inspection of the area appeared to confirm it.

Interior view of bomb shelter

Bomb shelter view looking out

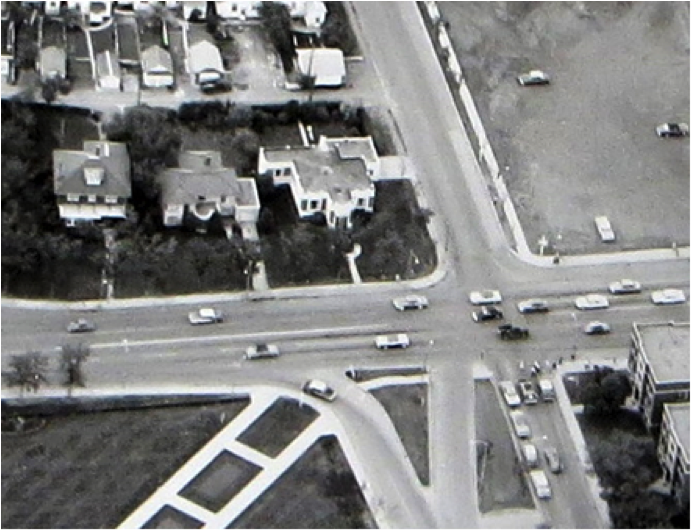

A heritage assessment requires discussion of the site’s history as it relates to the history of the region as well. And of immediate interest was the erstwhile north neighbour: 11 Leopold, which was entered into the City’s Building Permit Book in 1944, the same year 13 Leopold Crescent, was listed. By 1973, 11 Leopold had disappeared but 1959 aerial photographs indicate design elements similar to 13 Leopold, such as corner windows and a central projection terminated by a curved wall, probably the entrance and foyer, at the front. The house was built by Fred Solomon, uncle of Saskatchewan’s current Lieutenant Governor, Honourable Vaughn Solomon-Schofield.

Ariel view of the houses at 11 and 13 Leopold Crescent, 1959

Yet another aspect of the site’s history particularly intrigued construction historian Frank Korvemaker, one of the researchers. His investigation, for example, outlined the reason why the Watchler and Solomon homes were built in the mid-1940s, while the first homes in the Crescents area were built in 1910, followed by most of the others in the 1920s.

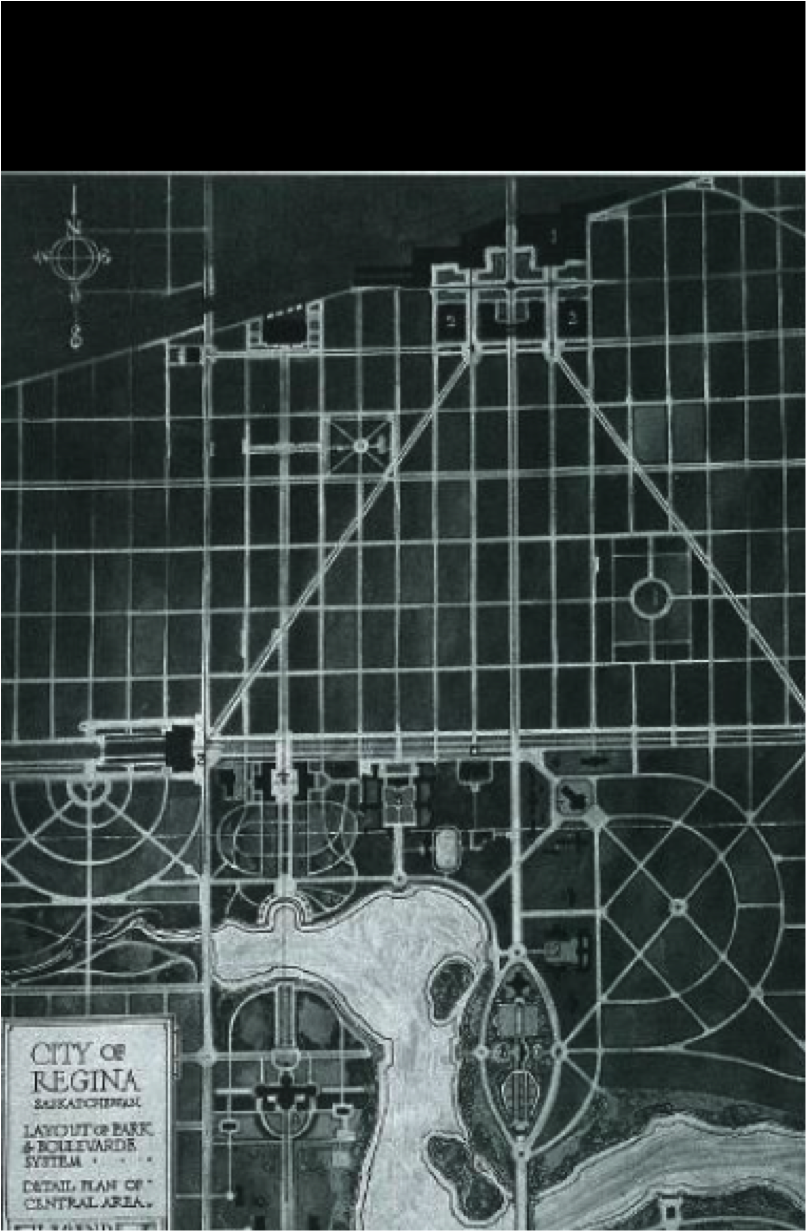

As Korvemaker explained, the layout of the Crescents originally appeared in 1882 as part of Regina’s first town survey. This plan was subsequently incorporated into the 1914 Mawson Plan for Wascana Park and its immediate surroundings. Thomas Henry Mawson, incidentally, was internationally well known for his urban landscape designs.

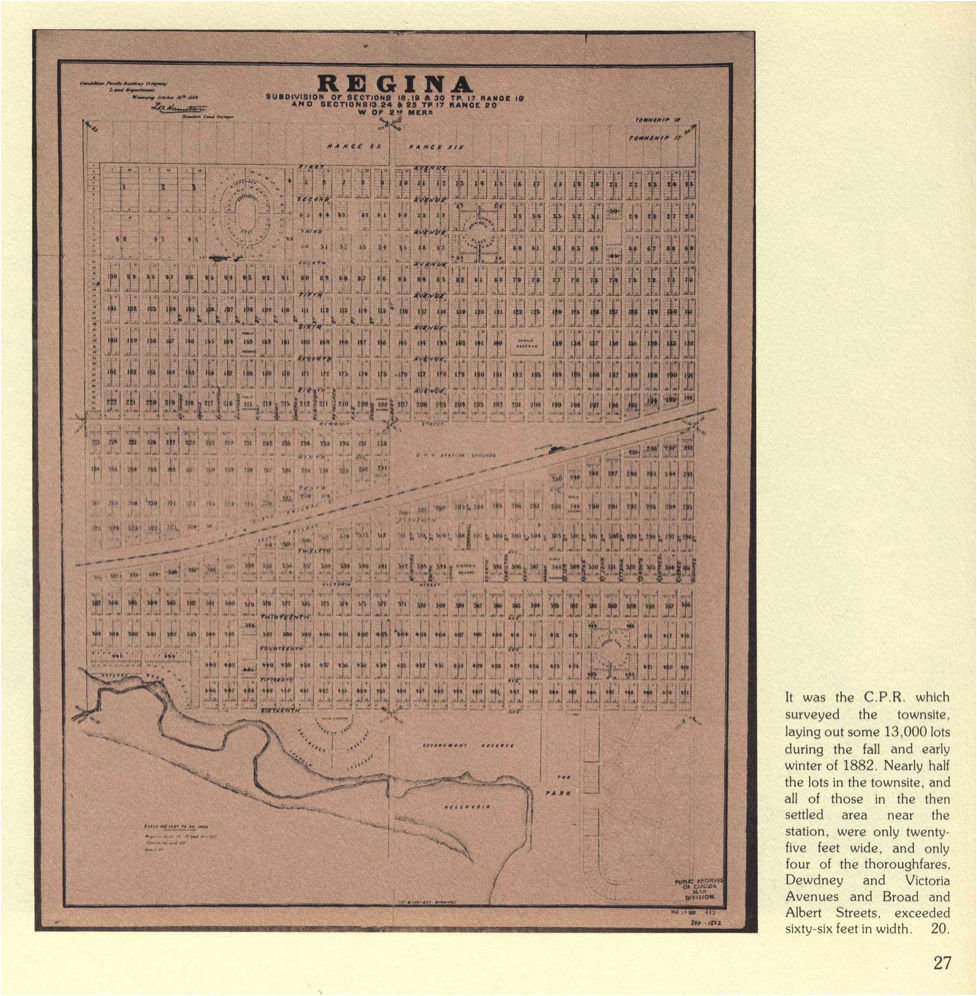

The C.P.R. surveyed the townsite laying out some 13,000 lots during the fall and early winter of 1882.

The properties serving as the major gateway to the Crescents, 11 and 13 Leopold Crescent, however, were not developed until 1945 because of the proposed location of a Grand Trunk Pacific Railway station at the northwest corner of College Avenue and Albert Street. A small temporary station was erected at this site in 1911, and its large, stone replacement, designed in the Chateau style to complement the GTP’s Chateau Qu’Appelle Hotel under construction on the southeast corner, was planned for the eastern terminus of the GTP’s line, which was to be built along College Avenue west of Albert Street.

City of Regina Plan 1914, showing location of the Grand Truck Pacific Railway and its proposed station at Albert St. and College Ave. Station bordering the northern boundary of The Crescents

The GTP station was to straddle the northwest and southwest corners of Albert and College but, in 1923, the GTP company was taken over by the federal government and merged with Canadian Northern Railway to form the Canadian National Railway. As a result, the plans for the GTP station were cancelled.

“Consequently, the encumbered southwest and northwest corner lots were apparently unavailable for new construction until sometime in the early- or mid-1940s and, by the time they finally went on the market, local architects and builders were incorporating elements of the latest international trends into their home designs. This accounts for the radical style difference between the Solomon and Watchler houses at 11 and 13 Leopold Crescent, and the other houses in The Crescents,” wrote Korvemaker in the research report.

Despite this fascinating history and unique design, and despite the best HR efforts to offer alternatives to demolition of 13 Leopold Crescent, however, the property owners have returned to their original plans to destroy the house and rebuild to their own design. City Planning Committee will officially review their request at their meeting on April 25th, 2016.

Architectural drawing of the proposed Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Station, to be situated at College Ave. and Albert Street, Regina.

Margaret Hryniuk (co-researcher)